How “Care” Compromises a Macalester Education

A faculty member at Macalester College takes issue with the administration's decision to "pause" Taravat Talepasand's art exhibit.

As many of my readers are aware, there has been another art controversy this year. This time it’s at Macalester College, just a stone’s throw from Hamline University which made national headlines for refusing to renew adjunct art history professor, Erika Lopez Prater’s contract. The reason: a Muslim student objected to her showing a 14th century Islamic painting of Muhammad in class. The Hamline debacle had barely passed when in early February Macalester “paused” an art exhibit on their campus — a retrospective exhibition of Iranian-American artist, Taravat Talepasand’s work. Some Muslim students claimed they were “harmed” by the art. Below I am reposting a letter that Arjun Guneratne, Professor of Anthropology, wrote to the editor of the Macalester newspaper in response to an article by a student. The student objected to Macalester’s decision to exhibit Talepasand’s work— artwork that the student referred to as “anti-Islamic art.” The student also referred to an email that the Macalester’s administration sent out just as students were returning to campus to begin the spring semester. In this email the administration announced that Erika Lopez Prater, who was at the center of the Hamline controversy, would be teaching art history at Macalester. The administration, in a tone that rings apologetic, took pains to note that Professor Prater was hired as an adjunct to teach at Macalester this semester before the Hamline controversy broke out. Now that you have some context, here is Arjun’s letter:

In his article in The Mac Weekly on Feb. 3 discussing the significance of showing images of the prophet of Islam in the classroom, Marouane El Bahraoui ’25 ends by writing, “Macalester’s decision to not only hire [Dr. López Prater] without context but to showcase anti-Islam art at Janet Wallace is inconsiderate to Islam and Muslims as a whole.” I must take issue with both of those assertions.

Dr. López Prater was hired because she is an art historian with impeccable credentials in her field. She enjoys the respect of her peers and has a record of successful teaching at Mac. Mac., moreover, has no obligation to “contextualize” its hires. Indeed, it would be improper of us to do so. A professor is at Mac because it is the judgment of the faculty that they will contribute to the academic mission of the college. It is the faculty that has the primary responsibility to determine who teaches here, not the administration. I was therefore troubled by the administration’s communication to the campus community on Jan. 12 about Dr. López Prater’s presence on campus. It focused invidious attention on a colleague who had done nothing to deserve it, by suggesting that her presence on campus somehow constituted a problem that might raise questions.

Mr. El Bahraoui makes reference to what happened at Hamline. That was not Dr. López Prater’s fault but the fault of Hamline’s administration, which acted without integrity to slander her. Their defamatory statement has been decisively rejected by public opinion; by Muslim scholars, including such conservative scholars as Dr. Shadee Elmasry of the Safinah Society; by public figures like Rep. Ilhan Omar (DFL-Minneapolis) (who has herself been the target of racist and Islamophobic attacks); and by Muslim organizations dedicated to fighting Islamophobia (like the national leadership of the Council of American Islamic Relations and the Muslim Public Affairs Council). Hamline has withdrawn its slander after being sued for defamation. That is the relevant context, omitted in Mr. El Bahraoui’s account.

He also objects to the art of Taravat Talepasand, the Iranian-American artist who was censored on campus. He says it is inconsiderate to Islam and Muslims as a whole. I respect his right to express his opinion, and I hope he will explain why he finds it objectionable. The artist, however, has the right to express her views. In a free society (such as the one Macalester seeks to model), she is entitled to not have her voice silenced in any way whatsoever. Whether her work is blasphemous or not is irrelevant. Blasphemy is a crime in many countries; it is in Sri Lanka, where I come from, where the ruling elite has preserved a colonial-era law because of its usefulness in controlling dissent. It is, however, not a crime in the United States, which is something about this country that I, as an immigrant, appreciate and celebrate.

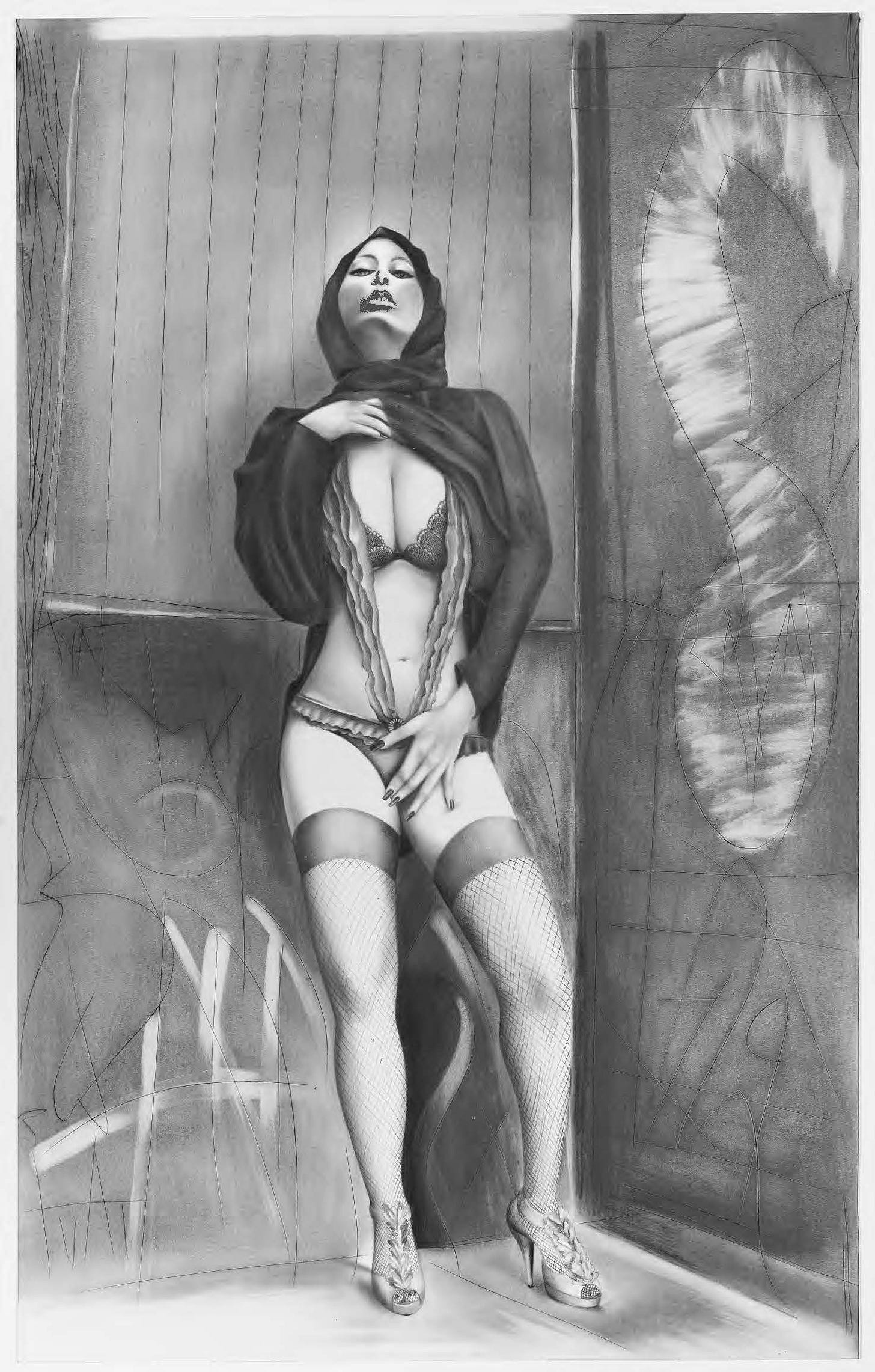

That Macalester has chosen to take sides on the issue of blasphemy in Islam — a matter for Muslims to work out among themselves and is none of Macalester’s business — is deeply troubling. It has been reported that Iranian students on campus supported Ms. Talepasand’s work and the exhibition, but their views apparently were considered less significant than those of students who had demanded censorship. That Macalester chose to censor Ms. Talepasand by concealing from view artwork in an exhibit that condemns the coerced veiling of women at the hands of a theocratic regime suggests that the administration did not reflect critically on the larger context in which its actions would be interpreted.

It is useful, however, to consider the language in which the administration announced this act of censorship. In an email to the community, the Provost and the Vice President for Institutional Equity state that “The pause provides space for members of our community who expressed pain caused by pieces in the exhibition.” Notably, there is no concern here with the pain caused to the artist by the censorship of her work nor the pain caused to those Iranians (students as well as members of the larger community) who saw the art as an expression of their own politics, which they might have wished to communicate to the world.

What interests me, however, is the rhetorical value of the word “pain,” along with other words like “hurt,” “trauma” and “harm,” that campus officials use to describe the impact on students of disconcerting or challenging ideas. If pain (or trauma or harm) is being caused, then of course, we should act to stop it. But do ideas cause “pain”?

Pain is everywhere in our world, but because we are discussing the censored exhibit, let us attend to Iran. The artist says her work “focuses on the plight of women, specifically from Iran.” The context, of course, is the uprising in Iran, precipitated by the murder in custody of a young woman for failing to wear her hijab according to the dictates of the state’s morality police, and led by women struggling to achieve political freedoms from a theocratic regime. Pain is what Iranian women who remove their veils and head coverings feel when they are beaten. Pain is caused every day to women and men in Iran, who are shot by the police when they demonstrate in the streets. Pain is what Iranians feel when they are raped and tortured in the regime’s prisons.

But when people at Macalester are offended by a graphite drawing that depicts a partially nude woman in a niqāb, what is being caused is not pain, but offense. In a free country, no one has the right to be exempt from being offended. Giving offense is a necessary byproduct of the freedom of speech and foundational to the existence of a free society, which the United States aspires to be. If the only free speech you are prepared to tolerate is the speech that doesn’t offend you, then effectively you don’t believe in free speech. That seems to be the administration’s position, framed in the language of “pain” and “care” as the reason to deny or to limit speech. As Hamline has found to its cost, censoring speech has profoundly negative consequences for the reputation of an institution. It garners deserved opprobrium.

Macalester, however, hasn’t always acted to censor speech when it offended the sensibilities of some students. Only last semester, for example, the college acted to protect the freedom of speech of the two participants in the Congress to Campus forum. On that occasion, two of my faculty colleagues wrote in the pages of this newspaper that the event was organized, “to help prepare our students to engage with others across sometimes radical difference. It is to help equip them to understand how “the other side” thinks, perhaps in order to better challenge them politically, perhaps merely in order to avoid dehumanizing or demonizing them. It is to enhance students’ political agency in a world where that matters.” The same sentiments apply in the present case. It is the responsibility of Macalester’s administration to help create a climate on campus in which the freedom to express ideas and conflicting points of view is fostered and safeguarded. By failing to do so in this instance, it has let all of us down.

In that context, and because Macalester’s values have been invoked in justifying this sorry affair, it is worth considering what those values are, as they have been communicated to students. This paragraph appears in the student handbook (4.1 Student Rights, Freedoms, and Responsibilities):

“Macalester College exists for the transmission of knowledge and the pursuit of truth. Free inquiry, free expression and responsibly free activity are indispensable to the attainment of these goals. Any assertion of rights and freedoms implies a readiness to assume concomitant responsibilities. The College community, in moving to protect individual liberty, expects from each of its members a recognition of the primarily academic purposes of the institution, a concern for the rights and freedoms of others, and a commitment to the rule of reason in the settling of disputes [emphasis added]. The purpose of the delineation of rights, freedoms and responsibilities that follows is to foster the growth of a free and cooperative community of learning.”

These are the values that must guide us, and we can achieve them only through a commitment to the freedom to discuss and debate ideas (including those communicated through art), however uncomfortable they make some members of our community. Indeed, if a student manages to complete a Macalester education without once having their fundamental beliefs challenged or being offended, it suggests the faculty hasn’t done its job properly. Our purpose as teachers is to educate our students (which is what constitutes our care of them). That requires that the faculty help students to engage the broad range of perspectives on any issue, so that their thinking and ours may be expanded, rather than merely accommodated. Where the freedom to do so is interfered with, as was the case at Hamline and now at Mac, the right of students to learn and develop skills of critical engagement with the kinds of complex issues they will encounter in their lives is undermined.

Arjun Guneratne is Professor of Anthropology at Macalester College. A version of this piece was originally published as a letter to the editor in Macalester College’s newspaper The Mac Weekly.

You may also like to read:

You Can’t Have Transformative Education Without Growing Pains

Let’s Face It: Academic Freedom and Inclusion Aren’t Always Compatible

"In a free country, no one has the right to be exempt from being offended." Great point.

If memory serves, under international law and custom, a right is something inherent and inviolate; whereas a liberty is granted and therefore subject to negotiation and removal.