You Can't Have Transformative Education Without Growing Pains

Macalester College's “pause” of a controversial art exhibit undermines the liberal arts.

“We upheld the principle of free inquiry, allowed time for important dialogue, and attended to the concerns of students who chose to make Macalester their intellectual home.” So wrote President Suzanne M. Rivera of Macalester College in a recent opinion piece for the Star Tribune, where she defended the college’s decision to “pause” a controversial campus art show in order to “prevent unintended viewing of the exhibit by passers-by.” The college’s actions were not an “infringement of academic and artistic freedom,” according to Rivera. Instead, Macalester managed to strike a balance between free expression and the “ethical responsibility to be kind to one another.”

For Rivera, Macalester’s approach successfully navigated “the complexities inherent in fostering a pluralistic community of learners.” We respectfully disagree. In our view, the leadership’s response has reinforced a counterproductive discourse of harm that undermines the liberal arts’ mission to foster curiosity, intellectual growth, and personal transformation.

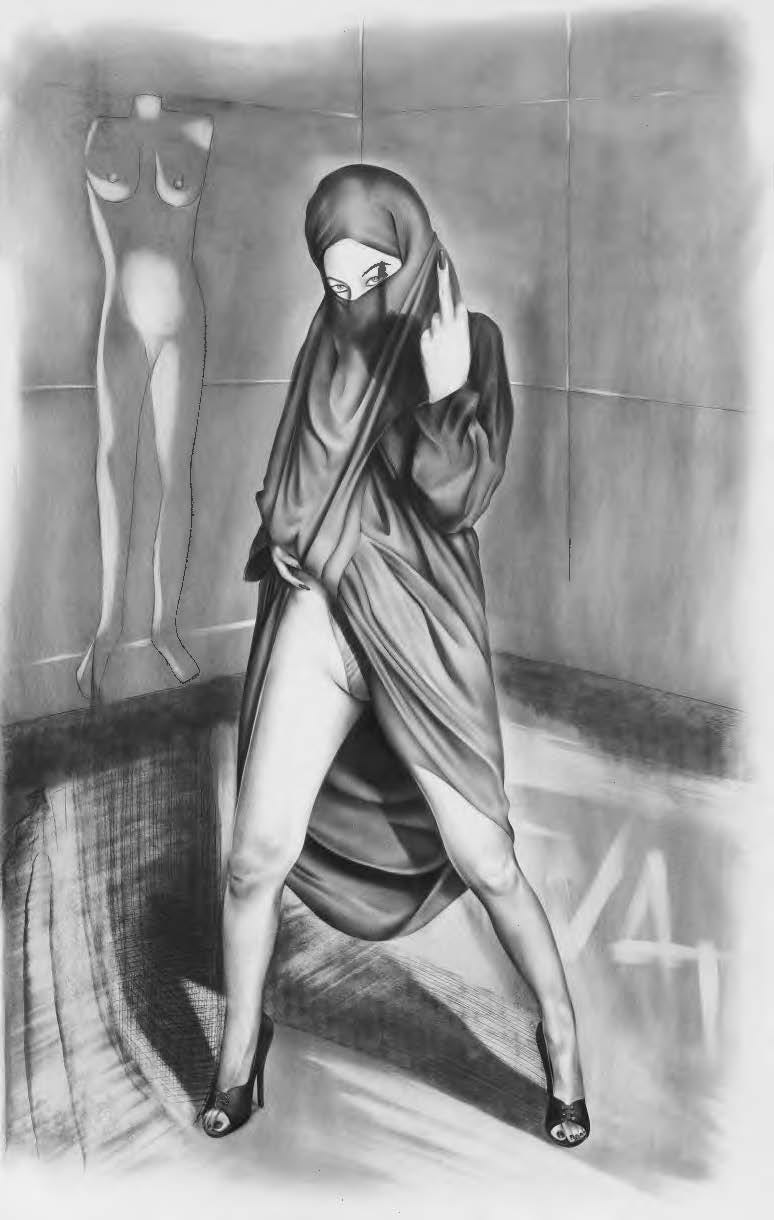

Let’s review what happened. On January 27, the college’s Law Warschaw Gallery opened TARAVAT, a retrospective of the Iranian American artist Taravat Talepasand’s “signature work from the last 15 years.” Her work, according to the gallery, “explores the cultural taboos that reflect on gender and political authority.” Some Muslim students objected to a series titled “Blasphemy” on the grounds that it was, well, blasphemous. One of the most “offensive” images, according to the students, was a graphite drawing of a veiled woman lifting her robe to expose lingerie underneath. Students complained in a petition that this image insulted the hijab, a sacred symbol of “god and faith to billions of Muslims everywhere,” and objectified Muslim women in a manner that was “disgusting, degrading, and dehumanizing.” (Talepasand herself said the series was about “autonomy” and “men not controlling women.”)

In response to student concerns, Macalester temporarily closed the exhibition and draped the glass walls of the gallery in heavy black curtains. The college then replaced the curtains with frosted glass and reopened the gallery with a posted advisory stating that the exhibit “contains images of sexuality and violence that may be upsetting or unacceptable for some visitors.”

The college announced the exhibit’s “pause” in an all-campus email sent by the provost, Lisa Anderson-Levy, and Alina Wong, vice president for institutional equity. Their message is a pitch-perfect expression of a safety-and-security model of education in which harm-mitigation is the preeminent value.

“It is with sadness,” Anderson-Levy and Wong wrote, “that we recognize the disrespect, disregard and invisibility that many in our Muslim community felt in response to the Taravat exhibition.”

“When harm is done,” they continued, “it is necessary that we pause.” A pause, the Macalester administrators explained, would provide “space for members of our community who expressed pain caused by pieces in the exhibition” and would give the gallery time to “consider ways in which unintentional viewing of works can be minimized.”

We see three problems with this approach. First, it signals to students that they have an emergency brake they can pull whenever they feel harmed. Second, it deals a blow to faculty confidence when it comes to teaching sensitive content. Who wants to court controversy and risk their professional reputation when colleges are so quick to hit the pause button if students feel offended or hurt?

Finally, it evades the question of what to do when a campus controversy results in conflicting claims of harm — which, as harm-claims become ever more incentivized by administrators, will surely happen more and more.

In her Star Tribune piece, Rivera celebrated the college’s “compassionate” response to the Muslim students upset by the exhibition. But what about Macalester community members who were upset by the pause itself? As reported in the college newspaper, one Iranian student said the hullabaloo surrounding the exhibit was “really frustrating and felt very invalidating.” She noted that the hijab was “something important, dear, and valuable” for the students who objected to the Blasphemy series. But for her, especially in light of the ongoing “woman, life, freedom!” protests in Iran, the hijab represents “something bad and controlling and censoring.” She summed up the divergent views as follows: “Our hearts were in different places.”

In their campus communications and public comments, none of Macalester’s leaders offered any meaningful defense of the gallery, the artist and her work, or, more broadly, the value of art in a liberal-arts education. The tone of the campuswide email is so forlorn and apologetic you get the sense that the provost and the VP for institutional equity are almost embarrassed that Macalester even has a fine-arts gallery. “As we create exhibitions and programs across global topics and cultural identities,” the email reads, “it is impossible to promise that future content will not be evocative or difficult.” This is a shocking declaration from a liberal-arts college whose mission statement proclaims that “education is a fundamentally transforming experience.” It runs counter to Macalester’s stated expectation that students will “develop the ability to seek and use knowledge and experience in contexts that challenge and inform their suppositions about the world.”

That’s why the impetus to reduce harm at every turn is so misguided. Surely challenges to students’ worldviews will necessitate growing pains. To help expand our horizons, we must create more, not fewer, opportunities to learn from the full range of human experience, for which there is nothing quite like art. “Looking at paintings,” the writer Jeanette Winterson says, is like “being dropped into a foreign city” that “follows its own customs and speaks its own language.” Art jolts us out of “ordinary life,” turns our world upside down, and “challenges the reality to which we lay claim.”

In the Star Tribune, Rivera took pains to emphasize that the Talepasand exhibit remains intact and has not been censored. But we find it hard to imagine that “a pause” like this one would not contribute to a censorious campus climate, in which the default setting is to avoid contention and discomfort.

To be clear, this piece is not a broadside against Macalester. We can imagine a similar sequence of events unfolding at virtually any college across the country. Campus blow-ups and “pauses” to deal with the accompanying fallout will only increase, given the prevalence of what we have in these pages called “DEI Inc.,” a cookie-cutter approach to managing campus diversity that is both exquisitely attuned to psychological harm and supremely risk averse. If colleges have any hope of staying true to the mission of liberal-arts education, their leaders need to affirm the importance of learning experiences that move students’ hearts and minds in ways that will evoke everything from delight to disgust.

A version of this piece was originally published on February 23, 2023 by The Chronicle of Higher Education.

You may also like to read:

How “Care” Compromises a Macalester Education

Let’s Face It: Academic Freedom and Inclusion Aren’t Always Compatible

"Censors to the left of me...banners to the right...Here I am stuck in the middle with you..."

Amna and Jeffrey, thank you for revisiting this. Macalester, my school of two years, tap-danced and think they won, because they weren’t Hamline University, but they lost. Everything Rivera did contributed to “supreme risk aversion” as you noted, and harm reduction. I have demanded since I saw those niqab curtains, then frosted windows, that a counterpoint exhibit was needed around the art building, preferably a chain link fence of Victoria’s Secret models popping out of their lingerie. Screw Macalester. Theo